Subtitles & vocabulary

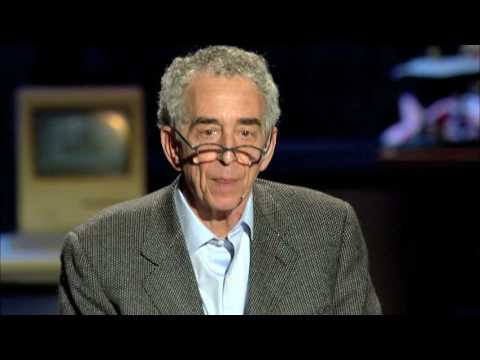

【TED】Barry Schwartz: Our loss of wisdom (Barry Schwartz: Our loss of wisdom)

00

Zenn posted on 2017/11/18Save

Video vocabulary

obvious

US /ˈɑbviəs/

・

UK /ˈɒbviəs/

- Adjective

- Easily understood and clear; plain to see

- Easy to see or notice.

A2TOEIC

More description

US /dɪˈskrɪpʃən/

・

UK /dɪˈskrɪpʃn/

- Noun

- Explanation of what something is like, looks like

- The type or nature of someone or something.

A2TOEIC

More crisis

US /ˈkraɪsɪs/

・

UK /'kraɪsɪs/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Unstable situation of extreme danger or difficulty

- A turning point in a disease.

B1

More experience

US /ɪkˈspɪriəns/

・

UK /ɪk'spɪərɪəns/

- Countable Noun

- Thing a person has done or that happened to them

- An event at which you learned something

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Knowledge gained by living life, doing new things

- Previous work in a particular field.

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters