Subtitles & vocabulary

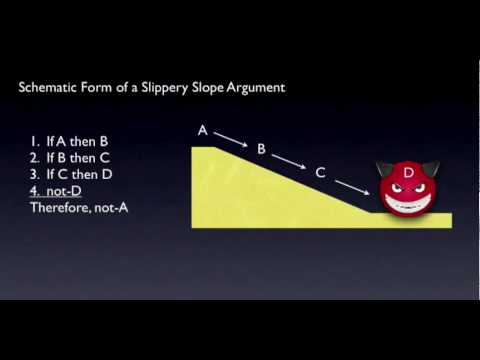

Fallacies: Slippery Slope

00

Keira Wang posted on 2017/12/12Save

Video vocabulary

vulnerable

US /ˈvʌlnərəbəl/

・

UK /ˈvʌlnərəbl/

- Adjective

- Being open to attack or damage

- Being easily harmed, hurt, or wounded

B1

More assume

US /əˈsum/

・

UK /ə'sju:m/

- Transitive Verb

- To act in a false manner to mislead others

- To believe, based on the evidence; suppose

A2TOEIC

More obvious

US /ˈɑbviəs/

・

UK /ˈɒbviəs/

- Adjective

- Easily understood and clear; plain to see

- Easy to see or notice.

A2TOEIC

More content

US /ˈkɑnˌtɛnt/

・

UK /'kɒntent/

- Adjective

- Being happy or satisfied

- In a state of peaceful happiness.

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Information in something, e.g. book or computer

- The subject matter of a book, speech, etc.

A2

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters