Subtitles & vocabulary

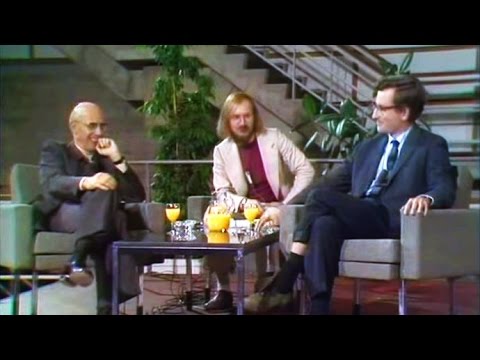

1971 Debate on Justice vs Power, Michel Foucault and Noam Chomsky

00

Kam Sut Mei posted on 2016/11/28Save

Video vocabulary

articulate

US /ɑ:rˈtɪkjuleɪt/

・

UK /ɑ:ˈtɪkjuleɪt/

- Transitive Verb

- To express something clearly using language

- Adjective

- Having or showing the ability to speak fluently and coherently.

B2TOEIC

More individual

US /ˌɪndəˈvɪdʒuəl/

・

UK /ˌɪndɪˈvɪdʒuəl/

- Countable Noun

- Single person, looked at separately from others

- A single thing or item, especially when part of a set or group.

- Adjective

- Made for use by one single person

- Having a distinct manner different from others

A2

More decent

US /ˈdisənt/

・

UK /ˈdi:snt/

- Adjective

- Being fairly good; acceptable

- Conforming to conventionally accepted standards of behaviour; respectable or moral.

B1

More concept

US /ˈkɑnˌsɛpt/

・

UK /'kɒnsept/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Abstract idea of something or how it works

- A plan or intention; a conception.

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters