Subtitles & vocabulary

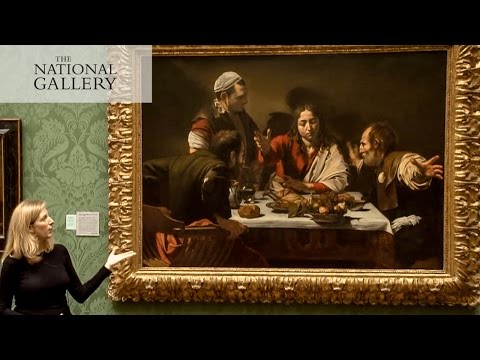

Caravaggio | You choose | The National Gallery, London

00

林容瑛 posted on 2016/09/14Save

Video vocabulary

sort

US /sɔrt/

・

UK /sɔ:t/

- Transitive Verb

- To organize things by putting them into groups

- To deal with things in an organized way

- Noun

- Group or class of similar things or people

A1TOEIC

More figure

US /ˈfɪɡjɚ/

・

UK /ˈfiɡə/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To appear in a game, play or event

- To calculate how much something will cost

- Noun

- Your body shape

- Numbers in a calculation

A1TOEIC

More time

US /taɪm/

・

UK /taɪm/

- Uncountable Noun

- Speed at which music is played; tempo

- Point as shown on a clock, e.g. 3 p.m

- Transitive Verb

- To check speed at which music is performed

- To choose a specific moment to do something

A1TOEIC

More expression

US /ɪkˈsprɛʃən/

・

UK /ɪk'spreʃn/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Act of making your thoughts and feelings known

- Group of words that have a specific meaning

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters