Subtitles & vocabulary

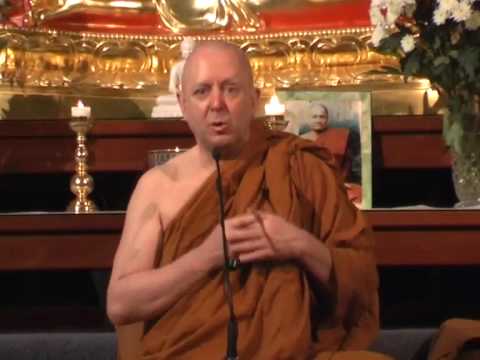

How To Be Positive | by Ajahn Brahm

00

Buddhima Xue posted on 2015/08/25Save

Video vocabulary

life

US /laɪf/

・

UK /laɪf/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- All the living things e.g. animals, plants, humans

- Period of time things live, from birth to death

A1

More people

US /ˈpipəl/

・

UK /'pi:pl/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Persons sharing culture, country, background, etc.

- Men, Women, Children

- Transitive Verb

- To populate; to fill with people.

A1

More beautiful

US /ˈbjutəfəl/

・

UK /'bju:tɪfl/

- Adjective

- Having dome something well

- Being very attractive or appealing physically

A1

More time

US /taɪm/

・

UK /taɪm/

- Uncountable Noun

- Speed at which music is played; tempo

- Point as shown on a clock, e.g. 3 p.m

- Transitive Verb

- To check speed at which music is performed

- To choose a specific moment to do something

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters