Subtitles & vocabulary

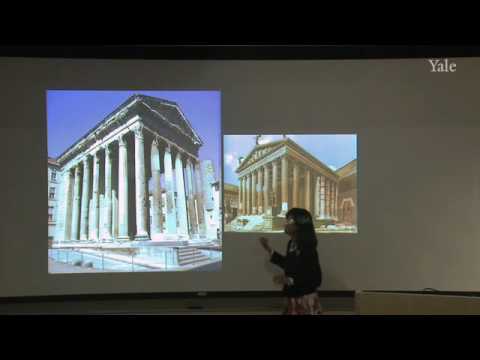

21. Making Mini Romes on the Western Frontier

00

Sofi posted on 2015/03/18Save

Video vocabulary

period

US /ˈpɪriəd/

・

UK /ˈpɪəriəd/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Set amount of time during which events take place

- A way to emphasize what you will say

A1TOEIC

More part

US /pɑ:rt/

・

UK /pɑ:t/

- Noun

- Division of a book

- Ratio of something, e.g. 3 of gin, 1 of tonic

- Transitive Verb

- To make a line in a person's hair, by using a comb

A1TOEIC

More interesting

US /ˈɪntrɪstɪŋ, -tərɪstɪŋ, -təˌrɛstɪŋ/

・

UK /ˈɪntrəstɪŋ/

- Adjective

- Taking your attention; making you want to know

- Remarkable or significant.

- Transitive Verb

- To make someone want to know about something

- To persuade to do, become involved with something

A1

More architecture

US /ˈɑrkɪˌtɛktʃɚ/

・

UK /ˈɑ:kɪtektʃə(r)/

- Uncountable Noun

- Design and construction of buildings

- The style or design of a building or buildings.

A2

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters