Subtitles & vocabulary

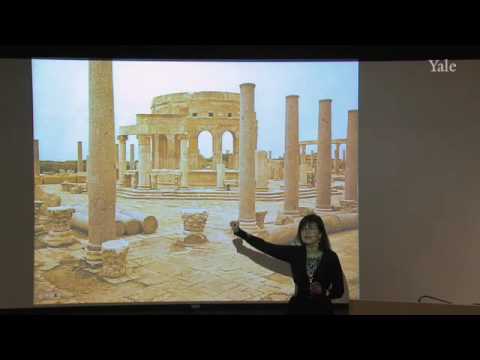

18. Hometown Boy: Honoring an Emperor's Roots in Roman North Africa

00

Sofi posted on 2015/03/17Save

Video vocabulary

structure

US /ˈstrʌk.tʃɚ/

・

UK /ˈstrʌk.tʃə/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- The way in which the parts of a system or object are arranged or organized, or a system arranged in this way

- A building or other man-made object.

- Transitive Verb

- To plan, organize, or arrange the parts of something

A2TOEIC

More interesting

US /ˈɪntrɪstɪŋ, -tərɪstɪŋ, -təˌrɛstɪŋ/

・

UK /ˈɪntrəstɪŋ/

- Adjective

- Taking your attention; making you want to know

- Remarkable or significant.

- Transitive Verb

- To make someone want to know about something

- To persuade to do, become involved with something

A1

More architecture

US /ˈɑrkɪˌtɛktʃɚ/

・

UK /ˈɑ:kɪtektʃə(r)/

- Uncountable Noun

- Design and construction of buildings

- The style or design of a building or buildings.

A2

More preserve

US /prɪˈzɜ:rv/

・

UK /prɪˈzɜ:v/

- Transitive Verb

- To cook food so it can be kept for long periods

- To protect something from harm, loss or damage

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Sweet fruit spread; jam

- Protected area of land with plants and animals

B1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters