Subtitles & vocabulary

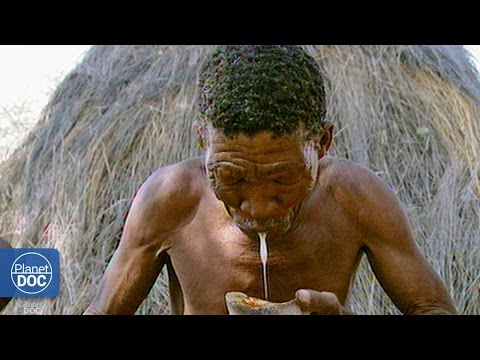

Desert of Skeletons. Full Documentary | Planet Doc Full Documentaries

00

realvip posted on 2014/10/15Save

Video vocabulary

territory

US /ˈtɛrɪˌtɔri, -ˌtori/

・

UK /'terətrɪ/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Area of land defended by an animal

- Area of particular knowledge or experience

B1TOEIC

More land

US /lænd/

・

UK /lænd/

- Uncountable Noun

- Region or country

- Earth; the ground

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To arrive or cause a boat to arrive at the shore

- To obtain or get something that you wanted

A1

More water

US /ˈwɔtɚ, ˈwɑtɚ/

・

UK /'wɔ:tə(r)/

- Uncountable Noun

- Clear liquid that forms the seas, rivers and rain

- Large area such as an ocean or sea

- Intransitive Verb

- (Of the eyes) to produce tears

- (Mouth) to become wet at the thought of nice food

A1

More remote

US /rɪˈmot/

・

UK /rɪ'məʊt/

- Adjective

- Being far away from people, towns, etc.

- (Of a possibility) being small or not likely

- Noun

- Radio device designed to operate TV, etc.

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters