Subtitles & vocabulary

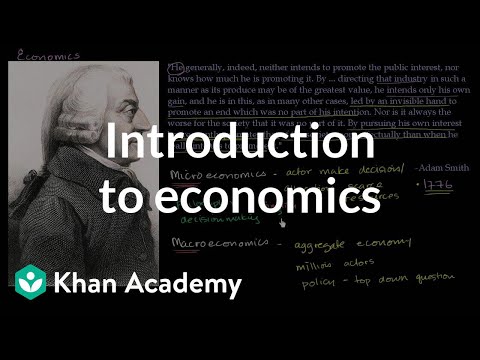

Introduction to Economics

00

Bravo001 posted on 2014/10/03Save

Video vocabulary

individual

US /ˌɪndəˈvɪdʒuəl/

・

UK /ˌɪndɪˈvɪdʒuəl/

- Countable Noun

- Single person, looked at separately from others

- A single thing or item, especially when part of a set or group.

- Adjective

- Made for use by one single person

- Having a distinct manner different from others

A2

More people

US /ˈpipəl/

・

UK /'pi:pl/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Persons sharing culture, country, background, etc.

- Men, Women, Children

- Transitive Verb

- To populate; to fill with people.

A1

More lead

US /lid/

・

UK /li:d/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Wire for electricity, computer, etc.; cable

- Information that could help to solve a crime

- Adjective

- Being the main part in movies or plays

A1TOEIC

More important

US /ɪmˈpɔrtnt/

・

UK /ɪmˈpɔ:tnt/

- Adjective

- Having power or authority

- Having a big effect on (person, the future)

- Uncountable Noun

- A matter of great significance.

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters