Subtitles & vocabulary

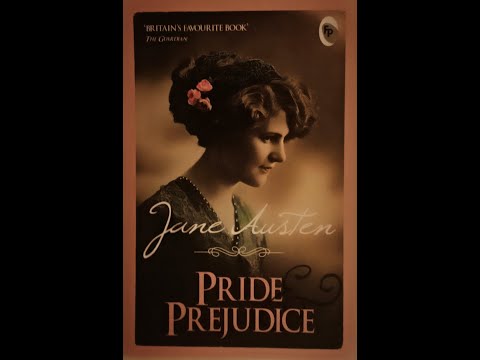

Pride & Prejudice | Chapter 1-5 (Audiobook)

00

林宜悉 posted on 2023/10/12Save

Video vocabulary

intimate

US /ˈɪntəmɪt/

・

UK /'ɪntɪmət/

- Adjective

- (E.g. of detail) fine, detailed or complete

- Private and personal things shared with another

- Transitive Verb

- To make someone understand without saying directly

B1TOEIC

More character

US /ˈkærəktɚ/

・

UK /'kærəktə(r)/

- Noun

- Person in a story, movie or play

- Writing symbols, e.g. alphabet or Chinese writing

A2

More compassion

US /kəmˈpæʃən/

・

UK /kəmˈpæʃn/

- Uncountable Noun

- Feeling of wanting to help suffering people

- Actions that demonstrate care and concern for others.

B2

More general

US /ˈdʒɛnərəl/

・

UK /'dʒenrəl/

- Adjective

- Widespread, normal or usual

- Not detailed or specific; vague.

- Countable Noun

- Top ranked officer in the army

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters