Subtitles & vocabulary

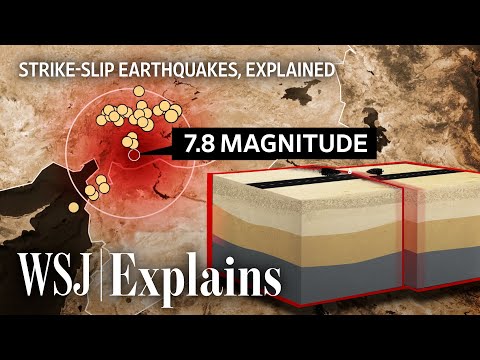

The Science Behind the Massive Turkey-Syria Earthquakes | WSJ

00

林宜悉 posted on 2023/02/19Save

Video vocabulary

vulnerable

US /ˈvʌlnərəbəl/

・

UK /ˈvʌlnərəbl/

- Adjective

- Being open to attack or damage

- Being easily harmed, hurt, or wounded

B1

More constantly

US /ˈkɑnstəntlɪ/

・

UK /ˈkɒnstəntli/

- Adverb

- Frequently, or without pause

- In a way that is unchanging or faithful

B1

More figure

US /ˈfɪɡjɚ/

・

UK /ˈfiɡə/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To appear in a game, play or event

- To calculate how much something will cost

- Noun

- Your body shape

- Numbers in a calculation

A1TOEIC

More devastating

US

・

UK

- Transitive Verb

- To cause extensive destruction or ruin utterly

- Adjective

- Destroying everything; very shocking

- Causing great emotional pain or shock.

B1

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters