Subtitles & vocabulary

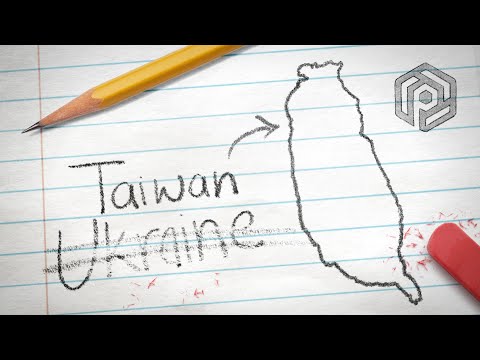

Why Taiwan is NOT Ukraine

00

王杰 posted on 2022/05/22Save

Video vocabulary

episode

US /ˈɛpɪˌsod/

・

UK /'epɪsəʊd/

- Noun

- One separate event in a series of events

- Show which is part of a larger story

B1TOEIC

More enormous

US /ɪˈnɔrməs/

・

UK /iˈnɔ:məs/

- Adjective

- Huge; very big; very important

- Very great in size, amount, or degree.

A2

More critical

US /ˈkrɪtɪkəl/

・

UK /ˈkrɪtɪkl/

- Adjective

- Making a negative judgment of something

- Being important or serious; vital; dangerous

A2

More crisis

US /ˈkraɪsɪs/

・

UK /'kraɪsɪs/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Unstable situation of extreme danger or difficulty

- A turning point in a disease.

B1

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters