Subtitles & vocabulary

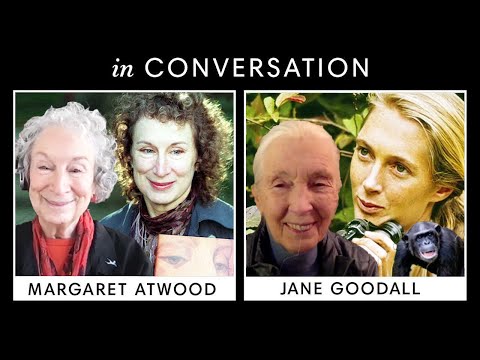

Jane Goodall & Margaret Atwood On Feminism, Climate Change, Racial Injustice | Harper’s BAZAAR

00

Summer posted on 2022/02/02Save

Video vocabulary

pandemic

US /pænˈdɛmɪk/

・

UK /pæn'demɪk/

- Adjective

- (of a disease) existing in almost all of an area or in almost all of a group of people, animals, or plants

- Noun

- a pandemic disease

C2

More period

US /ˈpɪriəd/

・

UK /ˈpɪəriəd/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Set amount of time during which events take place

- A way to emphasize what you will say

A1TOEIC

More positive

US /ˈpɑzɪtɪv/

・

UK /ˈpɒzətɪv/

- Adjective

- Showing agreement or support for something

- Being sure about something; knowing the truth

- Noun

- A photograph in which light areas are light and dark areas are dark

A2

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters