Subtitles & vocabulary

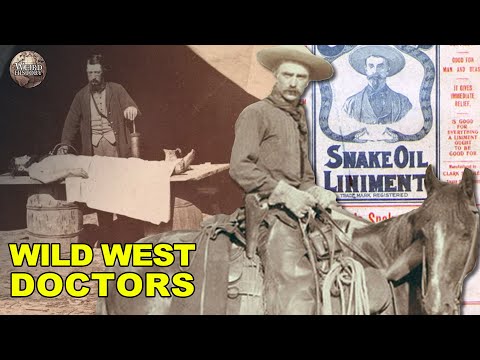

What It Was Like Going To A Doctor In Wild West

00

joey joey posted on 2021/05/21Save

Video vocabulary

weird

US /wɪrd/

・

UK /wɪəd/

- Adjective

- Odd or unusual; surprising; strange

- Eerily strange or disturbing.

B1

More sort

US /sɔrt/

・

UK /sɔ:t/

- Transitive Verb

- To organize things by putting them into groups

- To deal with things in an organized way

- Noun

- Group or class of similar things or people

A1TOEIC

More eventually

US /ɪˈvɛntʃuəli/

・

UK /ɪˈventʃuəli/

- Adverb

- After a long time; after many attempts; in the end

- At some later time; in the future

A2

More majority

US /məˈdʒɔrɪti, -ˈdʒɑr-/

・

UK /mə'dʒɒrətɪ/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Amount that is more than half of a group

- The age at which a person is legally considered an adult.

B1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters