Subtitles & vocabulary

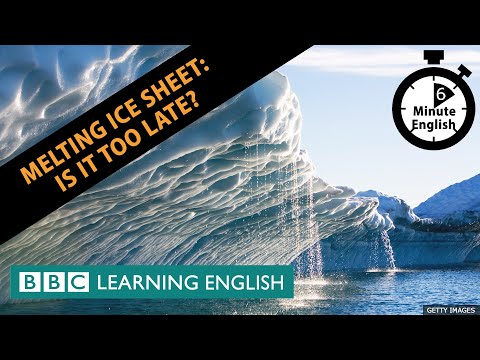

Melting ice sheet: Is it too late? - 6 Minute English

00

林宜悉 posted on 2020/11/05Save

Video vocabulary

situation

US /ˌsɪtʃuˈeʃən/

・

UK /ˌsɪtʃuˈeɪʃn/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Place, position or area that something is in

- An unexpected problem or difficulty

A1TOEIC

More vocabulary

US /voˈkæbjəˌlɛri/

・

UK /və'kæbjələrɪ/

- Uncountable Noun

- Words that have to do with a particular subject

- The words that a person knows

B1TOEIC

More convince

US /kənˈvɪns/

・

UK /kən'vɪns/

- Transitive Verb

- To persuade someone, or make them feel sure

A2TOEIC

More approximately

US /əˈprɑksəmɪtlɪ/

・

UK /əˈprɒksɪmətli/

- Adverb

- Around; nearly; almost; about (a number)

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters