Subtitles & vocabulary

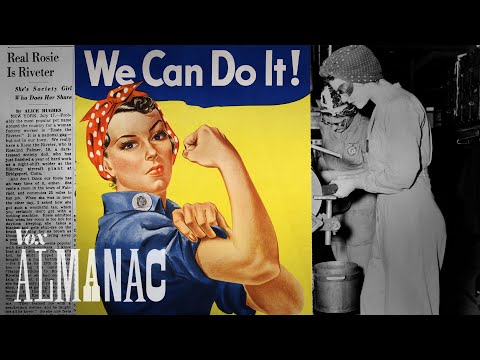

The real story behind this war poster

00

Lee Amanda posted on 2020/05/29Save

Video vocabulary

effort

US /ˈɛfət/

・

UK /ˈefət/

- Uncountable Noun

- Amount of work used trying to do something

- A conscious exertion of power; a try.

A2TOEIC

More decline

US /dɪˈklaɪn/

・

UK /dɪ'klaɪn/

- Intransitive Verb

- To bend towards the ground

- To slope downward.

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To lessen in quality or value

A2TOEIC

More advocate

US /ˈædvəˌket/

・

UK /'ædvəkeɪt/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- A lawyer who protects a clients interests

- Person who supports a movement for changes

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To request change

- To publicly support a belief

B1TOEIC

More ubiquitous

US /juˈbɪkwɪtəs/

・

UK /ju:ˈbɪkwɪtəs/

- Adjective

- Found everywhere; found in many places

C2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters