Subtitles & vocabulary

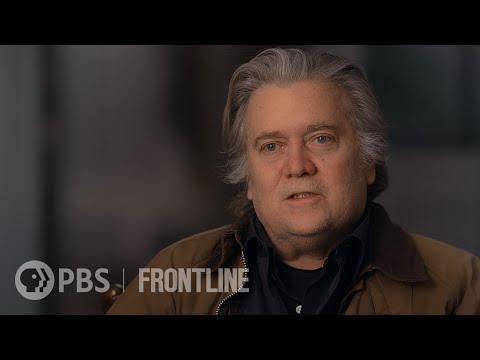

America's Great Divide: Steve Bannon, 1st Interview | FRONTLINE

00

Yeung-On Yu posted on 2020/05/25Save

Video vocabulary

stuff

US /stʌf/

・

UK /stʌf/

- Uncountable Noun

- Generic description for things, materials, objects

- Transitive Verb

- To push material inside something, with force

B1

More debate

US / dɪˈbet/

・

UK /dɪ'beɪt/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- General public discussion of a topic

- A formal event where two sides discuss a topic

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To consider options before making a decision

- To take part in a formal discussion

A2TOEIC

More crisis

US /ˈkraɪsɪs/

・

UK /'kraɪsɪs/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Unstable situation of extreme danger or difficulty

- A turning point in a disease.

B1

More campaign

US /kæmˈpen/

・

UK /kæm'peɪn/

- Intransitive Verb

- To work in an organized, active way towards a goal

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Series of actions meant to achieve a goal

- A planned set of military activities intended to achieve a particular objective.

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters