Subtitles & vocabulary

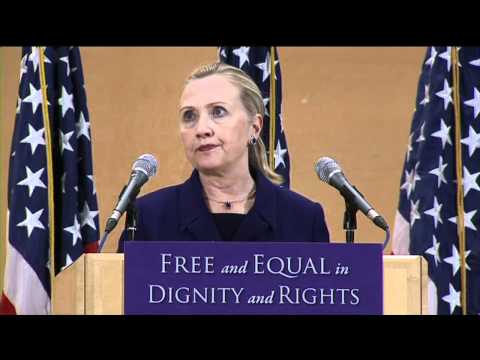

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's Historic LGBT Speech - Full Length - High Definition

00

Anne Sheu posted on 2014/03/12Save

Video vocabulary

people

US /ˈpipəl/

・

UK /'pi:pl/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Persons sharing culture, country, background, etc.

- Men, Women, Children

- Transitive Verb

- To populate; to fill with people.

A1

More treat

US /trit/

・

UK /tri:t/

- Transitive Verb

- To pay for the food or enjoyment of someone else

- To use medical methods to try to cure an illness

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Something you buy for others as a surprise present

- something that tastes good and that is not eaten often

A1TOEIC

More progress

US /ˈprɑɡˌrɛs, -rəs, ˈproˌɡrɛs/

・

UK /'prəʊɡres/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To move forward or toward a place or goal

- To make progress; develop or improve.

- Uncountable Noun

- Act of moving forward

- The process of improving or developing something over a period of time.

A2TOEIC

More work

US /wɚk/

・

UK /wɜ:k/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- The product of some artistic or literary endeavor

- Everything created by an author, artist, musician

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To bring into a specific state of success

- To be functioning properly, e.g. a car

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters