Subtitles & vocabulary

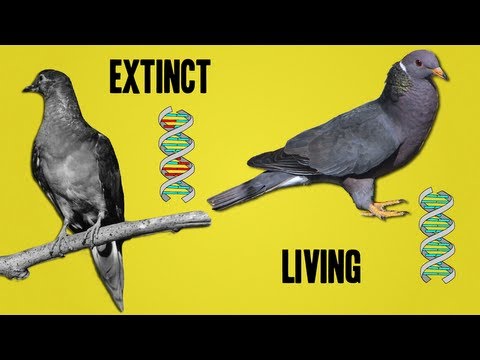

The Science Behind De-extinction

00

Bing-Je posted on 2013/12/10Save

Video vocabulary

close

US /kloʊz/

・

UK /kləʊz/

- Adjective

- Almost; near

- (Of a friend) well-known; liked by others

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To come progressively nearer to something

- To end; to bring to an end

A1

More living

US /ˈlɪvɪŋ/

・

UK /'lɪvɪŋ/

- Intransitive Verb

- To be alive

- To make your home in a house or town

- Adjective

- Alive

A1

More egg

US /ɛɡ/

・

UK /eg/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Hard-shelled thing from which a young bird is born

A2

More kind

US /kaɪnd/

・

UK /kaɪnd/

- Adjective

- In a caring and helpful manner

- Countable Noun

- One type of thing

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters