Subtitles & vocabulary

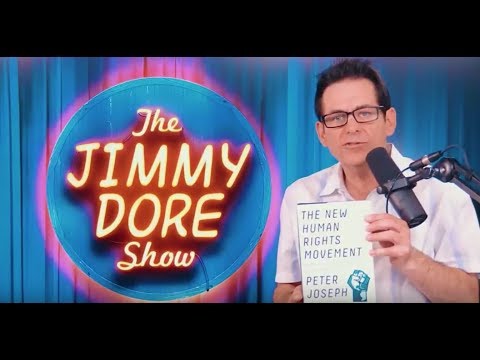

Peter Joseph with Jimmy Dore. Full Interview, April 2018 [ The Zeitgeist Movement ]

00

王惟惟 posted on 2018/11/29Save

Video vocabulary

stuff

US /stʌf/

・

UK /stʌf/

- Uncountable Noun

- Generic description for things, materials, objects

- Transitive Verb

- To push material inside something, with force

B1

More absolutely

US /ˈæbsəˌlutli, ˌæbsəˈlutli/

・

UK /ˈæbsəlu:tli/

- Adverb

- Completely; totally; very

- Considered independently and without relation to other things; viewed abstractly; as, quantity absolutely considered.

A2

More access

US /ˈæksɛs/

・

UK /'ækses/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Way to enter a place, e.g. a station or stadium

- The opportunity or right to use something or to see someone.

- Transitive Verb

- To be able to use or have permission to use

A2TOEIC

More progress

US /ˈprɑɡˌrɛs, -rəs, ˈproˌɡrɛs/

・

UK /'prəʊɡres/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To move forward or toward a place or goal

- To make progress; develop or improve.

- Uncountable Noun

- Act of moving forward

- The process of improving or developing something over a period of time.

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters