Subtitles & vocabulary

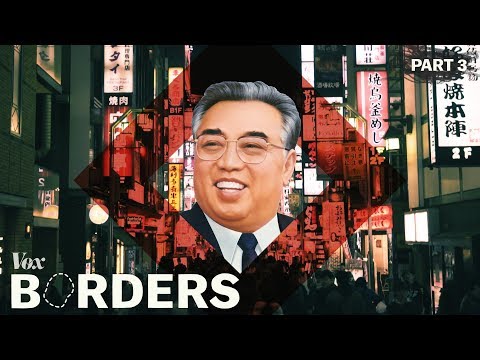

Inside North Korea's bubble in Japan

00

Samuel posted on 2018/03/19Save

Video vocabulary

cultivate

US /ˈkʌltəˌvet/

・

UK /'kʌltɪveɪt/

- Transitive Verb

- To grow plants, crops etc.

- To cause to grow by education; to enlighten

B1

More crave

US /krev/

・

UK /kreɪv/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To have a very strong desire for something

B2

More surge

US /sɜ:rdʒ/

・

UK /sɜ:dʒ/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Sudden movement in one direction by many

- Sudden or unexpected increase in amount

- Intransitive Verb

- To move unexpectedly and quickly in one direction

- To rise to an unexpected height

B2

More community

US /kəˈmjunɪti/

・

UK /kə'mju:nətɪ/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Group of people who share a common idea or area

- A feeling of fellowship with others, as a result of sharing common attitudes, interests, and goals.

- Adjective

- Relating to or shared by the people in a particular area.

- Shared or participated in by all members of a group

A2

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters