Subtitles & vocabulary

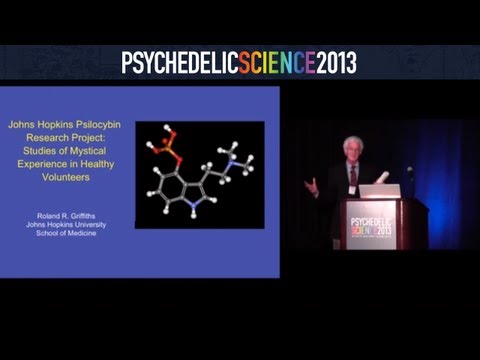

Johns Hopkins Psilocybin Research Project - Roland Griffiths

00

tom0615jay posted on 2017/05/08Save

Video vocabulary

meditation

US /ˌmɛdɪˈteʃən/

・

UK /ˌmedɪ'teɪʃn/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Act of deep and quiet thinking

- The practice of focusing one's mind for a period of time.

B2

More significant

US /sɪɡˈnɪfɪkənt/

・

UK /sɪgˈnɪfɪkənt/

- Adjective

- Large enough to be noticed or have an effect

- Having meaning; important; noticeable

A2TOEIC

More present

US /ˈprɛznt/

・

UK /'preznt/

- Adjective

- Being in attendance; being there; having turned up

- Being in a particular place; existing or occurring now.

- Noun

- Gift

- Verb tense indicating an action is happening now

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters