Subtitles & vocabulary

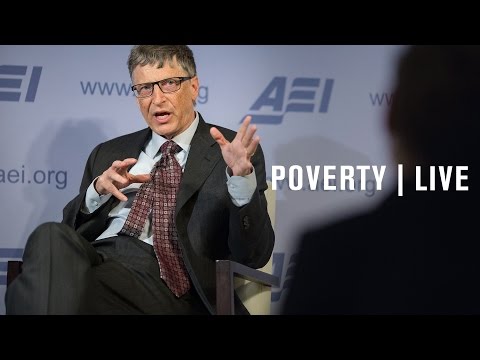

Bill Gates: A conversation on poverty and prosperity

00

Emily posted on 2016/07/02Save

Video vocabulary

people

US /ˈpipəl/

・

UK /'pi:pl/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Persons sharing culture, country, background, etc.

- Men, Women, Children

- Transitive Verb

- To populate; to fill with people.

A1

More world

US /wɜrld /

・

UK /wɜ:ld/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- All the humans, events, activities on the earth

- Political division due to some kind of similarity

A1

More work

US /wɚk/

・

UK /wɜ:k/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- The product of some artistic or literary endeavor

- Everything created by an author, artist, musician

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To bring into a specific state of success

- To be functioning properly, e.g. a car

A1TOEIC

More foundation

US /faʊnˈdeʃən/

・

UK /faunˈdeiʃən/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Base or important starting point

- Underground base on which building is constructed

C1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters