Subtitles & vocabulary

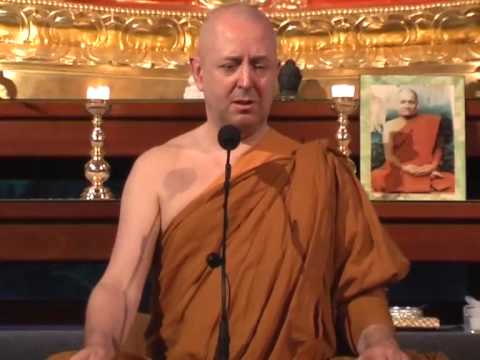

Freeing Problems in Life with Metta | by Ajahn Brahm

00

Buddhima Xue posted on 2015/08/25Save

Video vocabulary

problem

US /ˈprɑbləm/

・

UK /ˈprɒbləm/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Something difficult to deal with or causes trouble

- Question to show understanding of a math concept

- Adjective

- Causing trouble

A1

More person

US /'pɜ:rsn/

・

UK /'pɜ:sn/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Man, woman or child

- An individual, typically used to emphasize their distinct identity or role.

A1

More people

US /ˈpipəl/

・

UK /'pi:pl/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Persons sharing culture, country, background, etc.

- Men, Women, Children

- Transitive Verb

- To populate; to fill with people.

A1

More life

US /laɪf/

・

UK /laɪf/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- All the living things e.g. animals, plants, humans

- Period of time things live, from birth to death

A1

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters