Subtitles & vocabulary

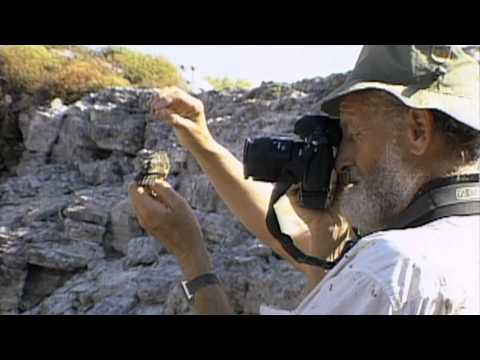

Galapagos Finch Evolution — HHMI BioInteractive Video

00

kevin posted on 2015/03/02Save

Video vocabulary

ground

US /ɡraʊnd/

・

UK /graʊnd/

- Transitive Verb

- To break (coffee, etc.) into tiny bits with machine

- To make sharp or smooth through friction

- Intransitive Verb

- To make loud jarring noise by pressing hard

- To hit the bottom

A1

More medium

US /ˈmidiəm/

・

UK /'mi:dɪəm/

- Noun

- Method of expressing ideas or feelings

- Something available in a middle size or condition

A2TOEIC

More offspring

US /ˈɔfˌsprɪŋ, ˈɑf-/

・

UK /'ɒfsprɪŋ/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Child or young of a person, plant or animal

- Something that results or is produced from something else.

- Noun (plural)

- Plural form of offspring.

B2

More diverse

US /dɪˈvɚs, daɪ-, ˈdaɪˌvɚs/

・

UK /daɪˈvɜ:s/

- Adjective

- Being varied or different from each other

- Very different from each other

B1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters