Subtitles & vocabulary

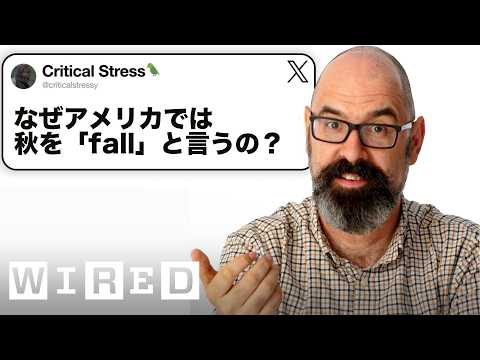

言語学者だけど「言葉の成り立ち」について質問ある? | Tech Support | WIRED Japan

00

林宜悉 posted on 2025/03/22Save

Video vocabulary

ultimately

US /ˈʌltəmɪtli/

・

UK /ˈʌltɪmətli/

- Adverb

- Done or considered as the final and most important

- Fundamentally; at the most basic level.

B1TOEIC

More period

US /ˈpɪriəd/

・

UK /ˈpɪəriəd/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Set amount of time during which events take place

- A way to emphasize what you will say

A1TOEIC

More ancient

US /ˈenʃənt/

・

UK /'eɪnʃənt/

- Adjective

- Very old; having lived a very long time ago

- Relating to a period in history, especially in the distant past.

- Noun

- A person who lived in ancient times.

A2

More tend

US /tɛnd/

・

UK /tend/

- Intransitive Verb

- To move or act in a certain manner

- Transitive Verb

- To take care of

A2

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters