Subtitles & vocabulary

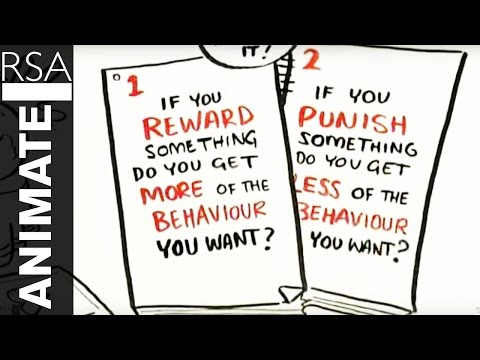

RSA Animate - Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us

00

稲葉白兎 posted on 2014/11/01Save

Video vocabulary

people

US /ˈpipəl/

・

UK /'pi:pl/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Persons sharing culture, country, background, etc.

- Men, Women, Children

- Transitive Verb

- To populate; to fill with people.

A1

More sophisticated

US /səˈfɪstɪˌketɪd/

・

UK /səˈfɪstɪkeɪtɪd/

- Adjective

- Making a good sounding but misleading argument

- Wise in the way of the world; having refined taste

- Transitive Verb

- To make someone more worldly and experienced

B1TOEIC

More work

US /wɚk/

・

UK /wɜ:k/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- The product of some artistic or literary endeavor

- Everything created by an author, artist, musician

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To bring into a specific state of success

- To be functioning properly, e.g. a car

A1TOEIC

More purpose

US /ˈpɚpəs/

・

UK /'pɜ:pəs/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Reason for which something is done; aim; goal

- A person's sense of resolve or determination.

- Adverb

- With clear intention or determination.

- Intentionally; deliberately.

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters