Subtitles & vocabulary

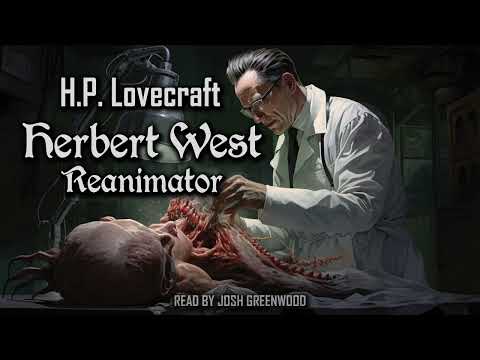

Herbert West – Reanimator by H.P. Lovecraft | Audiobook

00

林宜悉 posted on 2023/08/14Save

Video vocabulary

artificial

US /ˌɑrtəˈfɪʃəl/

・

UK /ˌɑ:tɪ'fɪʃl/

- Adjective

- Dishonest, to seem fake, not sincere

- (Something) made by people; not created by nature

B1TOEIC

More experiment

US /ɪkˈspɛrəmənt/

・

UK /ɪk'sperɪmənt/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Test performed to assess new ideas or theories

- A course of action tentatively adopted without being sure of the eventual outcome.

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To create and perform tests to research something

- To try something new that you haven't tried before

A2TOEIC

More fear

US /fɪr/

・

UK /fɪə(r)/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Unpleasant feeling caused by being aware of danger

- A feeling of reverence and respect for someone or something.

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To be afraid of or nervous about something

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters