Subtitles & vocabulary

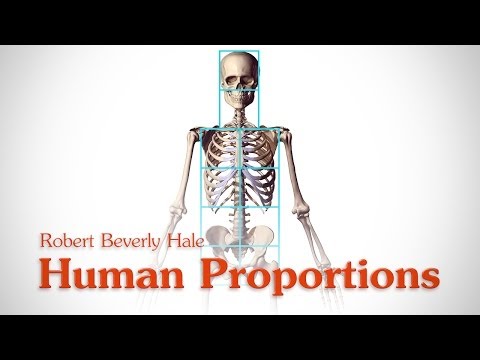

Human Figure Proportions - Cranial Units - Robert Beverly Hale

00

vulvul posted on 2014/09/22Save

Video vocabulary

head

US /hɛd/

・

UK /hed/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To hit a ball with your head in a game

- To be first or at the front or top (e.g. a list)

- Countable Noun

- Counter for the number of cattle

- Leader or person with the greatest authority

A1TOEIC

More measure

US /ˈmɛʒɚ/

・

UK /ˈmeʒə(r)/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Plan to achieve a desired result

- Tool used to calculate the size of something

- Transitive Verb

- To determine the value or importance of something

- To calculate size, weight or temperature of

A1TOEIC

More great

US /ɡret/

・

UK /ɡreɪt/

- Adverb

- Very good; better than before

- Adjective

- Very large in size

- Very important

A1TOEIC

More draw

US /drɔ/

・

UK /drɔ:/

- Transitive Verb

- To attract attention to someone or something

- To influence a person's involvement in something

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Something that attracts people to visit a place

- A lottery or prize

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters