Subtitles & vocabulary

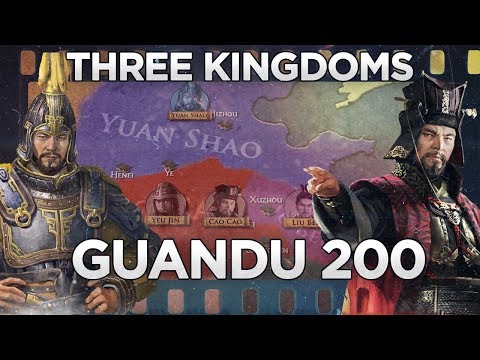

Battle of Guandu 200 - Three Kingdoms DOCUMENTARY

00

香蕉先生 posted on 2022/07/03Save

Video vocabulary

entire

US /ɛnˈtaɪr/

・

UK /ɪn'taɪə(r)/

- Adjective

- Complete or full; with no part left out; whole

- Undivided; not shared or distributed.

A2TOEIC

More massive

US /ˈmæsɪv/

・

UK /ˈmæsɪv/

- Adjective

- Very big; large; too big

- Large or imposing in scale or scope.

B1

More significant

US /sɪɡˈnɪfɪkənt/

・

UK /sɪgˈnɪfɪkənt/

- Adjective

- Large enough to be noticed or have an effect

- Having meaning; important; noticeable

A2TOEIC

More critical

US /ˈkrɪtɪkəl/

・

UK /ˈkrɪtɪkl/

- Adjective

- Making a negative judgment of something

- Being important or serious; vital; dangerous

A2

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters