Subtitles & vocabulary

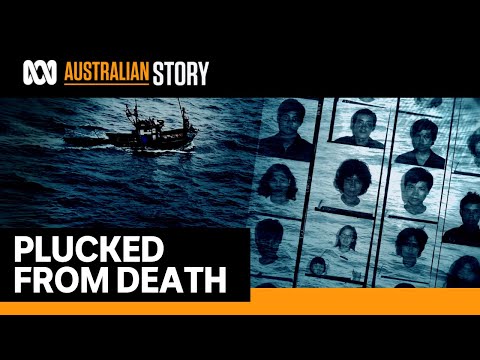

Stranded at sea, the Royal Australian Navy's daring rescue of the MG99 | Australian Story

00

joey joey posted on 2021/10/11Save

Video vocabulary

sort

US /sɔrt/

・

UK /sɔ:t/

- Transitive Verb

- To organize things by putting them into groups

- To deal with things in an organized way

- Noun

- Group or class of similar things or people

A1TOEIC

More absolutely

US /ˈæbsəˌlutli, ˌæbsəˈlutli/

・

UK /ˈæbsəlu:tli/

- Adverb

- Completely; totally; very

- Considered independently and without relation to other things; viewed abstractly; as, quantity absolutely considered.

A2

More treat

US /trit/

・

UK /tri:t/

- Transitive Verb

- To pay for the food or enjoyment of someone else

- To use medical methods to try to cure an illness

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Something you buy for others as a surprise present

- something that tastes good and that is not eaten often

A1TOEIC

More spot

US /spɑt/

・

UK /spɒt/

- Noun

- A certain place or area

- A difficult time; awkward situation

- Transitive Verb

- To see someone or something by chance

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters