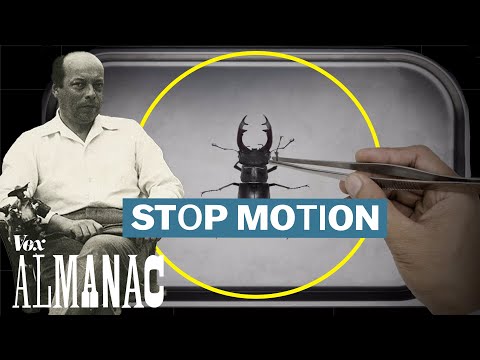

Subtitles & vocabulary

How stop motion animation began

00

林宜悉 posted on 2020/09/18Save

Video vocabulary

illusion

US /ɪˈluʒən/

・

UK /ɪ'lu:ʒn/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Idea, image or impression that is not correct

- Something that deceives by producing a false or misleading impression of reality.

B2

More experiment

US /ɪkˈspɛrəmənt/

・

UK /ɪk'sperɪmənt/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Test performed to assess new ideas or theories

- A course of action tentatively adopted without being sure of the eventual outcome.

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To create and perform tests to research something

- To try something new that you haven't tried before

A2TOEIC

More combination

US /ˌkɑmbəˈneʃən/

・

UK /ˌkɒmbɪ'neɪʃn/

- Noun

- Series of letters or numbers needed to open a lock

- Act or result of mixing things together

B1

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters