Subtitles & vocabulary

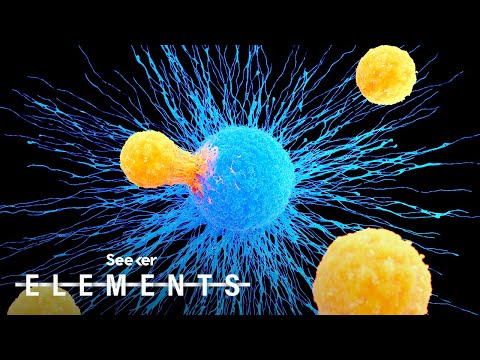

This Cell Might Hold the Answer to a Universal Cure for Cancer

00

Summer posted on 2020/08/28Save

Video vocabulary

specific

US /spɪˈsɪfɪk/

・

UK /spəˈsɪfɪk/

- Adjective

- Precise; particular; just about that thing

- Concerning one particular thing or kind of thing

A2

More potential

US /pəˈtɛnʃəl/

・

UK /pəˈtenʃl/

- Adjective

- Capable of happening or becoming reality

- Having or showing the capacity to develop into something in the future.

- Uncountable Noun

- someone's or something's ability to develop, achieve, or succeed

A2TOEIC

More immune

US /ɪˈmjoon/

・

UK /ɪˈmju:n/

- Adjective

- Having a special protection from, e.g. the law

- Protected against a particular disease or condition because of antibodies or vaccination.

B1

More recognize

US /ˈrek.əɡ.naɪz/

・

UK /ˈrek.əɡ.naɪz/

- Transitive Verb

- To accept the truth or reality of something

- To consider something as important or special

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters