Subtitles & vocabulary

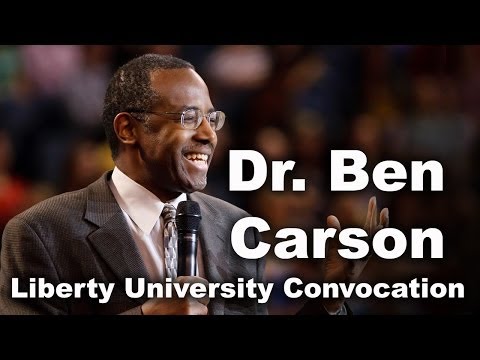

Ben Carson - Liberty University Convocation

00

Precious Annie Liao posted on 2014/05/03Save

Video vocabulary

time

US /taɪm/

・

UK /taɪm/

- Uncountable Noun

- Speed at which music is played; tempo

- Point as shown on a clock, e.g. 3 p.m

- Transitive Verb

- To check speed at which music is performed

- To choose a specific moment to do something

A1TOEIC

More people

US /ˈpipəl/

・

UK /'pi:pl/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Persons sharing culture, country, background, etc.

- Men, Women, Children

- Transitive Verb

- To populate; to fill with people.

A1

More brain

US /bren/

・

UK /breɪn/

- Transitive Verb

- To strike someone forcefully on the head

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- The part of the head that thinks

- A smart person who often makes good decisions

A1

More think

US /θɪŋk/

・

UK /θɪŋk/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To have an idea about something without certainty

- To have an idea, opinion or belief about something

A1

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters