Subtitles & vocabulary

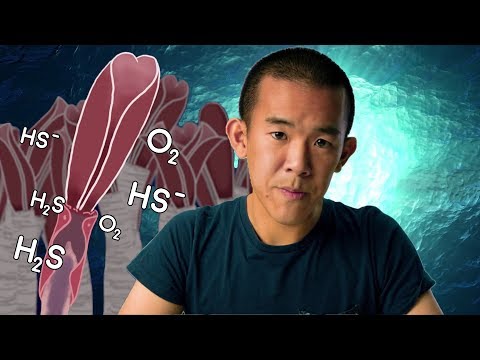

How Giant Tube Worms Survive at Hydrothermal Vents | I Contain Multitudes

00

王杰 posted on 2020/05/29Save

Video vocabulary

weird

US /wɪrd/

・

UK /wɪəd/

- Adjective

- Odd or unusual; surprising; strange

- Eerily strange or disturbing.

B1

More ultimately

US /ˈʌltəmɪtli/

・

UK /ˈʌltɪmətli/

- Adverb

- Done or considered as the final and most important

- Fundamentally; at the most basic level.

B1TOEIC

More process

US /ˈprɑsˌɛs, ˈproˌsɛs/

・

UK /prə'ses/

- Transitive Verb

- To organize and use data in a computer

- To deal with official forms in the way required

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Dealing with official forms in the way required

- Set of changes that occur slowly and naturally

A2TOEIC

More extreme

US /ɪkˈstrim/

・

UK /ɪk'stri:m/

- Adjective

- Very great in degree

- Farthest from a center

- Noun

- Effort that is thought more than is necessary

- The furthest point or limit of something.

B1

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters