Subtitles & vocabulary

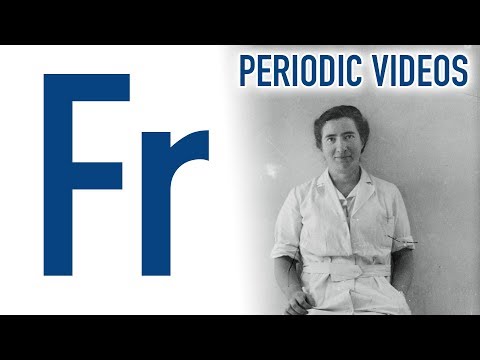

Francium - Periodic Table of Videos

00

林宜悉 posted on 2020/03/27Save

Video vocabulary

chronic

US /ˈkrɑnɪk/

・

UK /'krɒnɪk/

- Adjective

- Always or often doing something, e.g. lying

- (Of disease) over a long time; serious

B1

More material

US /məˈtɪriəl/

・

UK /məˈtɪəriəl/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Cloth; fabric

- Supplies or data needed to do a certain thing

- Adjective

- Relevant; (of evidence) important or significant

- Belonging to the world of physical things

A2

More realize

US /ˈriəˌlaɪz/

・

UK /'ri:əlaɪz/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To become aware of or understand mentally

- To achieve or make something happen.

A1TOEIC

More expect

US /ɪkˈspɛkt/

・

UK /ɪk'spekt/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To believe something is probably going to happen

- To anticipate or believe that something will happen or someone will arrive.

A1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters